Tatmadaw

| Myanmar Armed Forces (Tatmadaw) | |

|---|---|

| တပ်မတော် (Burmese) (lit. 'Grand Army') | |

_of_Myanmar.svg/220px-Flag_of_the_Armed_Forces_(Tatmadaw)_of_Myanmar.svg.png) Flag of the Myanmar Armed Forces | |

| |

| Founded | 27 March 1945[2] |

| Service branches | |

| Headquarters | Naypyidaw, Myanmar |

| Website | |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | Senior General Min Aung Hlaing |

| Deputy Commander-in-Chief | Vice-Senior General Soe Win |

| Minister of Defence | Admiral Tin Aung San |

| Joint Chief of Staff | General Maung Maung Aye[3] |

| Personnel | |

| Military age | 18 years of age |

| Available for military service | 14,747,845 males, age 15–49 (2010 est.), 14,710,871 females, age 15–49 (2010 est.) |

| Fit for military service | 10,451,515 males, age 15–49 (2010 est.), 11,181,537 females, age 15–49 (2010 est.) |

| Reaching military age annually | 522,478 males (2010 est.), 506,388 females (2010 est.) |

| Active personnel | about 150,000 personnel; 70,000 combat troops (May 2023 estimate)[4] |

| Reserve personnel | 18,998 (23 battalions of Border Guard Force, BGF (7498 personnel),[5] 46 groups of People's Militia Group, PMG and Regional People's Militia Groups, RPMG (3500 personnel)[5] five corps of university Training Corp, UTC (8000 personnel)[6] |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | $2.7 billion[7] (2023) |

| Percent of GDP | 4% (2014) |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers |

|

| Foreign suppliers | |

| Related articles | |

| Ranks | Military ranks of Myanmar |

Parliamentary Seats တပ်မတော်သား လွှတ်တော်ကိုယ်စားလှယ်များ (Burmese) | |

|---|---|

| Seats in the Amyotha Hluttaw | 56 / 224 |

| Seats in the Pyithu Hluttaw | 110 / 440 |

| Seats in the State Administration Council | 9 / 18 |

The Tatmadaw (Burmese: တပ်မတော်; MLCTS: tatma.taw, IPA: [taʔmədɔ̀], lit. 'Grand Army') is the military of Myanmar (formerly Burma). It is administered by the Ministry of Defence and composed of the Myanmar Army, the Myanmar Navy and the Myanmar Air Force. Auxiliary services include the Myanmar Police Force, the Border Guard Forces, the Myanmar Coast Guard, and the People's Militia Units.[13] Since independence in 1948, the Tatmadaw has faced significant ethnic insurgencies, especially in Chin, Kachin, Kayin, Kayah, and Shan states. General Ne Win took control of the country in a 1962 coup d'état, attempting to build an autarkic society called the Burmese Way to Socialism. Following the violent repression of nationwide protests in 1988, the military agreed to free elections in 1990, but ignored the resulting victory of the National League for Democracy and imprisoned its leader Aung San Suu Kyi.[14] The 1990s also saw the escalation of the conflict between Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State due to RSO attacks on Tatmadaw forces.

In 2008, the Tatmadaw again rewrote Myanmar's constitution, installing the pro-junta Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) in 2010 elections boycotted by most opposition groups. Political reforms over the next half-decade culminated in a sweeping NLD victory in the 2015 election;[15] after the USDP lost another election in 2020, the Tatmadaw annulled the election and deposed the civilian government. The Tatmadaw has been widely accused by international organizations of human rights violation and crimes against humanity; including ethnic cleansing,[16][17][18] political repression, torture, sexual assault, war crimes, extrajudicial punishments (including summary executions) and massacre of civilians involved in peaceful political demonstrations.[16][19][20] The Tatmadaw has long operated as a state within a state.[21][22]

According to the Constitution of Myanmar, the Tatmadaw directly reports to the National Defence and Security Council (NDSC) led by the President of Myanmar.[23] The NDSC is an eleven-member national security council responsible for security and defence affairs in Myanmar. As of 2023[update], the NDSC serves as the highest authority in the Government of Myanmar.

History[edit]

Burmese monarchy[edit]

The Royal Armed Forces was the armed forces of the Burmese monarchy from the 9th to 19th centuries. It refers to the military forces of the Pagan dynasty, the Ava Kingdom, the Toungoo dynasty and the Konbaung dynasty in chronological order. The army was one of the major armed forces of Southeast Asia until it was defeated by the British over a six-decade span in the 19th century.

The army was organised into a small standing army of a few thousand, which defended the capital and the palace, and a much larger conscription-based wartime army. Conscription was based on the ahmudan system, which required local chiefs to supply their predetermined quota of men from their jurisdiction on the basis of population in times of war. The wartime army also consisted of elephantry, cavalry, artillery and naval units.

Firearms, first introduced from China in the late 14th century, became integrated into strategy only gradually over many centuries. The first special musket and artillery units, equipped with Portuguese matchlocks and cannon, were formed in the 16th century. Outside the special firearm units, there was no formal training program for the regular conscripts, who were expected to have a basic knowledge of self-defence, and how to operate the musket on their own. As the technological gap between European powers widened in the 18th century, the army was dependent on Europeans' willingness to sell more sophisticated weaponry.

While the army had held its own against the armies of the kingdom's neighbours, its performance against more technologically advanced European armies deteriorated over time. While it defeated the Portuguese and French intrusions in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively, the army proved unable to match the military strength of the British Empire in the 19th century, losing the First, Second and Third Anglo-Burmese Wars. On 1 January 1886, the Royal Burmese Army was formally disbanded by the British government.

British Burma (1885–1948)[edit]

Under British rule, the colonial government in Burma abstained from recruiting Burmese soldiers into the East India Company forces (and later the British Indian Army), instead relying on pre-existing Indian sepoys and Nepalese Gurkhas to garrison the nascent colony. Due to mistrust of the Burmese population, the colonial government maintained this ban for decades, instead looking to the indigenous Karens, Kachins and Chins to form new military units in the colony. In 1937, the colonial government overturned the ban, and Burmese troops started to enlist in small numbers in the British Indian Army.[24]

At the beginning of the First World War, the only Burmese military regiment in the British Indian Army, the 70th Burma Rifles, consisted of three battalions, made up of Karens, Kachins and Chins. During the conflict, the demands of war led to the colonial government relaxing the ban, raising a Burmese battalion in the 70th Burma Rifles, a Burmese company in the 85th Burma Rifles, and seven Burmese Mechanical Transport companies. In addition, three companies (combat units) of Burma Sappers and Miners, made up of mostly Burmese, and a company of Labour Corps, made up of Chins and Burmese, were also raised. All these units began their overseas assignment in 1917. The 70th Burma Rifles served in Egypt for garrison duties while the Burmese Labour Corps served in France. One company of Burma Sappers and Miners distinguished themselves in Mesopotamia at the crossing the Tigris.[25][26]

After the First World War, the colonial government stopped recruiting Burmese soldiers, and discharged all but one Burmese companies, which had been abolished by 1925. The last Burmese company of Burma Sappers and Miners too was disbanded in 1929.[25] Instead, Indian soldiers and other ethnic minorities were used as the primary colonial force in Burma, which was used to suppress ethnic Burmese rebellions such as the one led by Saya San from 1930 to 1931. On 1 April 1937, Burma was made a separate colony, and Burmese were now eligible to join the army. But few Burmese bothered to join. Before World War II began, the British Burma Army consisted of Karen (27.8%), Chin (22.6%), Kachin (22.9%), and Burmese 12.3%, without counting their British officer corps.[27]

In December 1941, a group of Burmese independence activists founded the Burma Independence Army (BIA) with Japanese help. The Burma Independence Army led by Aung San (the father of Aung San Su Kyi) fought in the Burma Campaign on the side of the Imperial Japanese Army. Thousands of young men joined its ranks—reliable estimates range from 15,000 to 23,000. The great majority of the recruits were Burmese, with little ethnic minority representation. Many of the fresh recruits lacked discipline. At Myaungmya in the Irrawaddy delta, an ethnic war broke out between Burmese BIA men and Karens, with both sides responsible for massacres. The BIA was soon replaced with the Burma Defence Army, founded on 26 August 1942 with three thousand BIA veterans. The army became Burma National Army with Ne Win as its commander on 1 August 1943 when Burma achieved nominal independence. In late 1944, it had a strength of approximately 15,000.[28]

Disillusioned by the Japanese occupation, the BNA switched sides, and joined the allied forces on 27 March 1945.

Post-independence[edit]

At the time of Myanmar's independence in 1948, the Tatmadaw was weak, small and disunited. Cracks appeared along the lines of ethnic background, political affiliation, organisational origin and different services. The most serious problem was the tension between Karen Officers, coming from the British Burma Army and Burmese officers, coming from the Patriotic Burmese Force (PBF).[citation needed]

In accordance with the agreement reached at the Kandy Conference in September 1945, the Tatmadaw was reorganised by incorporating the British Burma Army and the Patriotic Burmese Force. The officer corps shared by ex-PBF officers and officers from the British Burma Army and Army of Burma Reserve Organisation (ABRO). The colonial government also decided to form what were known as "Class Battalions" based on ethnicity. There were a total of 15 rifle battalions at the time of independence and four of them were made up of former members of PBF. None of the influential positions within the War Office and commands were manned with former PBF Officers. All services including military engineers, supply and transport, ordnance and medical services, Navy and Air Force were commanded by former Officers from ABRO and British Burma Army.[citation needed]

| Battalion | Ethnic/Army Composition |

|---|---|

| No. 1 Burma Rifles | Bamar (Military Police + Members of Taungoo Guerilla group members associated with Aung San's PBF) |

| No. 2 Burma Rifles | 2 Karen Companies + 1 Chin Company and 1 Kachin Company |

| No. 3 Burma Rifles | Bamar / Former members of Patriotic Burmese Force – Commanded by then Major Kyaw Zaw BC-3504 |

| No. 4 Burma Rifles | Bamar / Former members of Patriotic Burmese Force – Commanded by the then Lieutenant Colonel Ne Win BC-3502 |

| No. 5 Burma Rifles | Bamar / Former members of Patriotic Burmese Force – Commanded by then Lieutenant Colonel Zeya BC-3503 |

| No. 6 Burma Rifles | Formed after Aung San was assassinated in later part of 1947, Bamar / Former members of Patriotic Burmese Force – First CO was Lieutenant Colonel Zeya |

| No. 1 Karen Rifles | Karen / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 2 Karen Rifles | Karen / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 3 Karen Rifles | Karen / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 1 Kachin Rifles | Kachin / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 2 Kachin Rifles | Kachin / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 1 Chin Rifles | Chin / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 2 Chin Rifles | Chin / Former members of British Burma Army and ABRO |

| No. 4 Burma Regiment | Gurkha |

| Chin Hill Battalion | Chin |

The War Office was officially opened on 8 May 1948 under the Ministry of Defence and managed by a War Office Council chaired by the Minister of Defence.[30] At the head of War Office was Chief of Staff, Vice Chief of Staff, Chief of Naval Staff, Chief of Air Staff, Adjutant General and Quartermaster General. Vice Chief of Staff, who was also Chief of Army Staff and the head of General Staff Office. VCS oversee General Staff matters and there were three branch offices: GS-1 Operation and Training, GS-2 Staff Duty and Planning; GS-3 Intelligence. Signal Corps and Field Engineering Corps are also under the command of General Staff Office.[31]

According to the war establishment adopted on 14 April 1948, Chief of Staff was under the War Office with the rank of major general. It was subsequently upgraded to a lieutenant general. Vice Chief of Staff was a brigadier general. The Chief of Staff was staffed with GSO-I with the rank of lieutenant colonel, three GSO-II with the rank of major, four GSO-III with the rank of captain for operation, training, planning and intelligence, and one Intelligence Officer (IO). The Chief of Staff office also had one GSO-II and one GSO-III for field engineering, and the Chief Signal Officer and a GSO-II for signal. Directorate of Signal and Directorate Field Engineering are also under General Staff Office.[31]

Under Adjutant General Office were Judge Advocate General, Military Secretary, and Vice Adjutant General. The Adjutant General (AG) was a brigadier general whereas the Judge Advocate General (JAG), Military Secretary (MS) and Vice Adjutant General (VAG) were colonels. VAG handles adjutant staff matters and there were also three branch offices; AG-1 planning, recruitment and transfer; AG-2 discipline, moral, welfare, and education; AG-3 salary, pension, and other financial matters. The Medical Corps and the Provost Marshal Office were under the Adjutant General Office.[31]

The Quarter Master General office also had three branch offices: QG-1 planning, procurement, and budget; QG-2 maintenance, construction, and cantonment; and QG-3 transportation. Under the QMG office were Garrison Engineering Corps, Electrical and Mechanical Engineering Corps, Military Ordnance Corps, and the Supply and Transport Corps.[31]

Both AG and QMG office similar structure to the General Staff Office, but they only had three ASO-III and three QSO-III respectively.[31]

The Navy and Air Force were separate services under the War office but under the chief of staff.[31]

| Post | Name and Rank | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| Chief of Staff | Lieutenant General Smith Dun BC 5106 | Karen |

| Chief of Army Staff | Brigadier General Saw Kyar Doe BC 5107 | Karen |

| Chief of Air Staff | Lieutenant Colonel Saw Shi Sho BAF-1020 | Karen |

| Chief of Naval Staff | Commander Khin Maung Bo | Bamar |

| North Burma Sub District Commander | Brigadier General Ne Win BC 3502 | Bamar |

| South Burma Sub District Commander | Brigadier General Aung Thin BC 5015 | Bamar |

| 1st Infantry Division | Brigadier General Saw Chit Khin | Karen |

| Adjutant General | Lieutenant Colonel Kyaw Win | Bamar |

| Judge Advocate General | Colonel Maung Maung (Bull dog) BC 4034 | Bamar |

| Quarter Master General | Lieutenant Colonel Saw Donny | Karen |

Reorganisation in 1956[edit]

As per War Office order No. (9) 1955 on 28 September 1955, the Chief of Staff became the Commander in Chief, the Chief of Army Staff became the Vice Chief of Staff (Army), the Chief of Naval Staff become Vice Chief of Staff (Navy) and the Chief of Air Staff became the Vice Chief of Staff (Air).[citation needed]

On 1 January 1956, the War Office was officially renamed as the Ministry of Defence. General Ne Win became the first Chief of Staff of the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) to command all three services – Army, Navy and Air Force – under a single unified command for the first time.[citation needed]

Brigadier General Aung Gyi was given the post of Vice Chief of Staff (Army). Brigadier General D. A Blake became commander of South Burma Subdistrict Command (SBSD) and Brigadier General Kyaw Zaw, a member of the Thirty Comrades, became Commander of North Burma Subdistrict Command (NBSD).[citation needed]

Caretaker government[edit]

Due to deteroriating political situations in 1957, the then prime minister of Burma, U Nu invited General Ne Win to form a "Caretaker Government" and handed over power on 28 October 1958. Under the stewardship of the Military Caretaker Government, parliamentary elections were held in February 1960. Several high-ranking and senior officers were dismissed due to their involvement and supporting various political parties.[33]

| Serial | Name and Rank | Command | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BC3505 | Brigadier Aung Shwe | Commander, Southern Burma Sub-District Command | 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3507 | Brigadier Maung Maung | Director of Directorate of Military Training / Commandant, National Defence College | 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3512 | Colonel Aye Maung | No. 2 Infantry Brigade | 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3517 | Colonel Tin Maung | No. 12 Infantry Brigade | 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3570 | Colonel Hla Maw | No. 5 Infantry Brigade | 13 February 1961 | Father of Thein Hla Maw |

| BC3572 | Colonel Kyi Win | No. 7 Infantry Brigade | 8 March 1961 | |

| BC3647 | Colonel Thein Tote | No. 4 Infantry Brigade | 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3181 | Lieutenant Colonel Kyaw Myint | 23 June 1962 | No. 10 Infantry Brigade // 13 February 1961 | |

| BC3649 | Lieutenant Colonel Chit Khaing | Deputy Commandant, Combat Forces School | 13 February 1962 |

1962 coup d'état[edit]

The elections of 1960 had put U Nu back as the Prime Minister and Pyidaungsu Party (Union Party) led civilian government resume control of the country.

On 2 March 1962, the then Chief of Staff of Armed Forces, General Ne Win staged a coup d'état and formed the "Union Revolutionary Council".[35] Around midnight the troops began to move into Yangon to take up strategic position. Prime Minister U Nu and his cabinet ministers were taken into protective custody. At 8:50 am, General Ne Win announced the coup over the radio. He said "I have to inform you, citizens of the Union that Armed Forces have taken over the responsibility and the task of keeping the country's safety, owing to the greatly deteriorating conditions of the Union." [36]

The country would be ruled by the military for the next 12 years. The Burma Socialist Programme Party became the sole political party and the majority of its full members were military.[37] Government servants underwent military training and the Military Intelligence Service functioned as the secret police of the state.

1988 coup d'état[edit]

At the height of the Four Eights Uprising against the socialist government, Former General Ne Win, who at the time was chairman of the ruling Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP), issued a warning against potential protestors during a televised speech. He stated that if the "disturbances" continued the "Army would have to be called and I would like to make it clear that if the Army shoots, it has no tradition of shooting into the Air, it would shoot straight to hit".[38]

Subsequently, the 22 Light Infantry Division, 33 Light Infantry Division and the 44 Light Infantry Division were redeployed to Yangon from front line fighting against ethnic insurgents in the Karen states. Battalions from three Light Infantry Divisions, augmented by infantry battalions under Yangon Regional Military Command and supporting units from Directorate of Artillery and Armour Corps were deployed during the suppression of protests in and around the then capital city of Yangon.

Initially, these troops were deployed in support of the then People's Police Force (now known as Myanmar Police Force) security battalions and to patrol the streets of the capital and to guard government offices and building. However, at midnight of 8 August 1988 troops from 22 Light Infantry Division guarding Yangon City Hall opened fire on unarmed protesters as the crackdown against the protests began.

The armed forces under General Saw Maung formed a State Law and Order Restoration Council, repealed the constitution and declared martial law on 18 September 1988. By late September the military had complete control of the country.

Political reforms (2008–2020)[edit]

In 2008, the current constitution was released by the military government for a public referendum. The SPDC claimed that the referendum was a success, with an approval rate of 93.82%; however, there has been widespread criticism of the veracity of these claims, partially because Cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar a few days before the referendum, and the government did not allow postponement of the referendum.[39] Under the 2008 Constitution, the Tatmadaw is guaranteed 25% of the seats in the parliament, making it difficult to pass meaningful reforms that the Tatmadaw does not approve of.

In 2010, conscription legislation was passed that compelled able-bodied men and women between 18–45 and 18–35 respectively to serve up to three years in the military, or face significant jail sentences.[40]

Following Myanmar's political reforms, Myanmar has made substantial shifts in its relations with major powers China, Russia and the United States.[41] In 2014, Lieutenant-General Anthony Crutchfield, the deputy commander of the United States Pacific Command (USPACOM), was invited to address his counterparts at the Myanmar National Defence College in Naypyidaw, which trains colonels and other high-ranking military officers.[42] In May 2016, Myanmar's Union Parliament approved a military cooperation agreement with Russia following a proposal by Deputy Minister of Defence.[43] In June 2016, Myanmar and Russia signed a defence cooperation agreement.[44] The agreement will envisage exchanging information on international security issues, including fight against terrorism, cooperation in the sphere of culture and vacation of servicemen and their families, along with exchanging experience in peacekeeping activities.

Moreover, in response to Naypyidaw's post-2011 political and economic reforms, Australia re-established a ‘normal’ bilateral relationship with Myanmar to support democratisation and reform. In June 2016, the Australian Federal Police signed a new Memorandum of Understanding with its Myanmar counterparts aimed at enhancing transnational crime cooperation and intelligence sharing.[45] In December 2017, the US imposed sanctions on General Maung Maung Soe, a general of Western Myanmar Command who oversaw the military's crackdown in Rakhine State. The Tatmadaw had sentenced seven soldiers to 10-year prison terms for killing 10 Rohingya men in Rakhine in September 2017.[46] A 2019 UN report revealed the degree to which the country's military uses its own businesses, foreign companies and arms deals to support, away from the public eye, a “brutal operations” against ethnic groups that constitute “serious crimes under international law”, bypassing civilian oversight and evading accountability.[47] In June 2020, the Tatmadaw accused China for arming rebel groups in the country's frontier areas.[48]

2021 coup d'état and aftermath[edit]

In February 2021, the Tatmadaw detained Aung San Suu Kyi and other high-ranking politicians after a contested election with disputed results. A state of emergency had been declared for one year.[49] The State Administration Council was established by Min Aung Hlaing on 2 February 2021 as the current government in power. On 1 August 2021, the State Administration Council was re-formed as a caretaker government, which appointed Min Aung Hlaing as prime minister.[50][51] The same day, Min Aung Hlaing announced that the country's state of emergency had been extended by an additional two years.[52]

As the Myanmar Civil War has progressed, the Tatmadaw has become more reliant on military aid from Russia and China.[53][54] As of 2023, analysts suggested that the Tatmadaw has sustained significant losses due to both combat against the pro-democracy insurgents as well as desertions within the rank and file soldiers. The United States Institute for Peace estimates that the Tatamadaw has sustained at least 13,000 combat losses and 8,000 losses due to desertion.[55] The Tatmadaw itself has acknowledged that it does not have control over 132 of Myanmar’s 330 townships, or 42 percent of the country's towns.[56][57]

Budget[edit]

According to an analysis of budgetary data between FY 2011–12 and 2018–19, approximately 13% to 14% of the national budget is devoted to the Burmese military.[58] However, the military budget remains opaque and subject to limited civilian scrutiny, and a 2011 Special Funds Law has enabled the Burmese military to circumvent parliamentary oversight to access supplemental funding.[59] Defence budgets were publicly shared for the first time in 2015, and in recent years, parliamentary lawmakers have demanded greater transparency in military spending.[59][60]

The military also generates substantial revenue through 2 conglomerates, the Myanma Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) and the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC).[61] Revenues generated from these business interests have strengthened the Burmese military's autonomy from civilian oversight, and have contributed to the military's financial operations in "a wide array of international human rights and humanitarian law violations."[61] Revenues from MEHL and MEC are kept "off-book," enabling the military to autonomously finance military affairs with limited civilian oversight.[62]

Between 1990 and 2020, Myanmar's military officers received US$18 billion in dividends from MEHL, whose entire board is made up of senior military officials.[63]

In the FY 2019–20 national budget, the military was allocated 3,385 billion kyats (approximately US$2.4 billion).[64] In May 2020, the Burmese parliament reduced the military's supplementary budgetary request by $7.55 million.[65] On 28 October 2014, the Minister for Defence Wai Lwin revealed at a Parliament session that 46.2% of the budget is spent on personnel cost, 32.89% on operation and procurement, 14.49% on construction related projects and 2.76% on health and education.[66]

Doctrine[edit]

Post-independence/civil war era (1948–1958)[edit]

The initial development of Burmese military doctrine post-independence was developed in the early 1950s to cope with external threats from more powerful enemies with a strategy of Strategic Denial under conventional warfare. The perception of threats to state security was more external than internal threats. The internal threat to state security was managed through the use of a mixture of force and political persuasion. Lieutenant Colonel Maung Maung drew up defence doctrine based on conventional warfare concepts, with large infantry divisions, armoured brigades, tanks and motorised war with mass mobilisation for the war effort being the important element of the doctrine.[33]

The objective was to contain the offensive of the invading forces at the border for at least three months, while waiting for the arrival of international forces, similar to the police action by international intervention forces under the directive of United Nations during the war on Korean peninsula. However, the conventional strategy under the concept of total war was undermined by the lack of appropriate command and control system, proper logistical support structure, sound economic bases and efficient civil defence organisations.[33]

Kuomintang invasion/Burma Socialist Programme Party era (1958–1988)[edit]

At the beginning of the 1950s, while the Tatmadaw was able to reassert its control over most part of the country, Kuomintang (KMT) troops under General Li Mi, with support from the United States, invaded Burma and used the country's frontier as a springboard for attack against China, which in turn became the external threat to state security and sovereignty of Burma. The first phase of the doctrine was tested for the first time in Operation "Naga Naing" in February 1953 against invading KMT forces. The doctrine did not take into account logistic and political support for KMT from the United States and as a result it failed to deliver its objectives and ended in a humiliating defeat for the Tatmadaw.[33]

The then Tatmadaw leadership argued that the excessive media coverage was partly to blame for the failure of Operation "Naga Naing". For example, Brigadier General Maung Maung pointed out that newspapers, such as the "Nation", carried reports detailing the training and troops positioning, even went as far to the name and social background of the commanders who are leading the operation thus losing the element of surprise. Colonel Saw Myint, who was second in command for the operation, also complained about the long lines of communications and the excessive pressure imposed upon the units for public relations activities to prove that the support of the people was behind the operation.[33]

Despite failure, the Tatmadaw continued to rely on this doctrine until the mid-1960s. The doctrine was under constant review and modifications throughout KMT invasion and gained success in anti-KMT operations in the mid and late 1950s. However, this strategy became increasingly irrelevant and unsuitable in the late 1950s as the insurgents and KMT changed their positional warfare strategy to hit and run guerrilla warfare.[67][68]

At the 1958 Tatmadaw's annual Commanding Officers (COs) conference, Colonel Kyi Win submitted a report outlining the requirement for new military doctrine and strategy. He stated that 'Tatmadaw did not have a clear strategy to cope with insurgents', even though most of Tatmadaw's commanders were guerrilla fighters during the anti-British and anti-Japanese campaigns during the Second World War, they had very little knowledge of anti-guerrilla or counterinsurgency warfare. Based upon Colonel Kyi Win's report, the Tatmadaw began developing an appropriate military doctrine and strategy to meet the requirements of counterinsurgency warfare.

This second phase of the doctrine was to suppress insurgency with people's war and the perception of threats to state security was more of internal threats. During this phase, external linkage of internal problems and direct external threats were minimised by the foreign policy based on isolation. It was common view of the commanders that unless insurgency was suppressed, foreign interference would be highly probable,[69] therefore counterinsurgency bec[70]ame the core of the new military doctrine and strategy. Beginning in 1961, the Directorate of Military Training took charge the research for national defence planning, military doctrine and strategy for both internal and external threats. This included reviews of international and domestic political situations, studies of the potential sources of conflicts, collection of information for strategic planning and defining the possible routes of foreign invasion.[33]

In 1962, as part of new military doctrine planning, principles of anti-guerrilla warfare were outlined and counterinsurgency-training courses were delivered at the training schools. The new doctrine laid out three potential enemies and they are internal insurgents, historical enemies with roughly an equal strength (i.e. Thailand), and enemies with greater strength. It states that in suppressing insurgencies, Tatmadaw must be trained to conduct long-range penetration with a tactic of continuous search and destroy. Reconnaissance, Ambush and all weather day and night offensive and attack capabilities along with winning the hearts and minds of people are important parts of anti-guerrilla warfare. For countering an historical enemy with equal strength, Tatmadaw should fight a conventional warfare under total war strategy, without giving up an inch of its territory to the enemy. For powerful enemy and foreign invaders, Tatmadaw should engage in total people's war, with a special focus on guerrilla strategy.[33]

To prepare for the transition to the new doctrine, Brigadier General San Yu, the then Vice Chief of Staff (Army), sent a delegation led by Lieutenant Colonel Thura Tun Tin was sent to Switzerland, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and East Germany in July 1964 to study organisation structure, armaments, training, territorial organisation and strategy of people's militias. A research team was also formed at General Staff Office within the War Office to study defence capabilities and militia formations of neighbouring countries.

The new doctrine of total people's war, and the strategy of anti-guerrilla warfare for counterinsurgency and guerrilla warfare for foreign invasion, were designed to be appropriate for Burma. The doctrine flowed from the country's independent and active foreign policy, total people's defence policy, the nature of perceived threats, its geography and the regional environment, the size of its population in comparison with those of its neighbours, the relatively underdeveloped nature of its economy and its historical and political experiences.

The doctrine was based upon 'three totalities': population, time and space (du-thone-du) and 'four strengths': manpower, material, time and morale (Panama-lay-yat). The doctrine did not develop concepts of strategic denial or counter-offensive capabilities. It relied almost totally on irregular low-intensity warfare, such as its guerrilla strategy to counter any form of foreign invasion. The overall counterinsurgency strategy included not only elimination of insurgents and their support bases with the 'four cut' strategy, but also the building and designation of 'white area' and 'black area' as well.

In April 1968, the Tatmadaw introduced special warfare training programmes at "Command Training Centres" at various regional commands. Anti-Guerrilla warfare tactics were taught at combat forces schools and other training establishments with special emphasis on ambush and counter-ambush, counterinsurgency weapons and tactics, individual battle initiative for tactical independence, commando tactics, and reconnaissance. Battalion size operations were also practised in the Southwest Regional Military Command area. The new military doctrine was formally endorsed and adopted at the first party congress of the BSPP in 1971.[citation needed] BSPP laid down directives for "complete annihilation of the insurgents as one of the tasks for national defence and state security" and called for "liquidation of insurgents through the strength of the working people as the immediate objective". This doctrine ensures the role of Tatmadaw at the heart of national policy making.

Throughout the BSPP era, the total people's war doctrine was solely applied in counterinsurgency operations, since Burma did not face any direct foreign invasion throughout the period. In 1985, the then Lieutenant General Saw Maung, Vice-Chief of Staff of Tatmadaw reminded his commanders during his speech at the Command and General Staff College:

In Myanmar, out of nearly 35 million people, the combined armed forces (army, navy and air force) are about two hundred thousand. In terms of percentage, that is about 0.01%. It is simply impossible to defend a country the size of ours with only this handful of troops... therefore, what we have to do in the case of foreign invasion is to mobilise people in accordance with the "total people's war" doctrine. To defend our country from aggressors, the entire population must be involved in the war effort as the support of people dictate the outcome of the war.

SLORC/SPDC era (1988–2010)[edit]

The third phase of doctrinal development of the Myanmar Armed Forces came after the military take over and formation of the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) in September 1988 as part of the armed forces modernisation programme. The development was the reflection of sensitivity towards direct foreign invasion or invasion by proxy state during the turbulent years of the late 1980s and early 1990s, for example: the unauthorised presence of a US aircraft carrier Battle Group in Myanmar's territorial waters during the 1988 political uprising as evidence of an infringement of Myanmar's sovereignty. Also, the Tatmadaw leadership was concerned that foreign powers might arm the insurgents on the border to exploit the political situation and tensions in the country. This new threat perception, previously insignificant under the nation's isolationist foreign policy, led Tatmadaw leaders to review the defence capability and doctrine of the Tatmadaw.[71]

The third phase was to face the lower level external threats with a strategy of strategic denial under total people's defence concept. Current military leadership has successfully dealt with 17 major insurgent groups, whose 'return to legal fold' in the past decade has remarkably decreased the internal threats to state security, at least for the short and medium terms, even though threat perception of the possibility of external linkage to internal problems, perceived as being motivated by the continuing human rights violations, religious suppression and ethnic cleansing, remains high.[71]

Within the policy, the role of the Tatmadaw was defined as a `modern, strong and highly capable fighting force'. Since the day of independence, the Tatmadaw has been involved in restoring and maintaining internal security and suppressing insurgency. It was with this background that Tatmadaw's "multifaceted" defence policy was formulated and its military doctrine and strategy could be interpreted as defence-in-depth. It was influenced by a number of factors such as history, geography, culture, economy and sense of threats.[71]

The Tatmadaw has developed an 'active defence' strategy based on guerrilla warfare with limited conventional military capabilities, designed to cope with low intensity conflicts from external and internal foes, which threatens the security of the state. This strategy, revealed in joint services exercises, is built on a system of total people's defence, where the armed forces provide the first line of defence and the training and leadership of the nation in the matter of national defence.[71]

It is designed to deter potential aggressors by the knowledge that defeat of the Tatmadaw's regular forces in conventional warfare would be followed by persistent guerrilla warfare in the occupied areas by people militias and dispersed regular troops which would eventually wear down the invading forces, both physically and psychologically, and leave it vulnerable to a counter-offensive. If the conventional strategy of strategic denial fails, then the Tatmadaw and its auxiliary forces will follow Mao's strategic concepts of 'strategic defensive', 'strategic stalemate' and 'strategic offensive'.[71]

Over the past decade, through a series of modernisation programs, the Tatmadaw has developed and invested in better Command, Control, Communication and Intelligence system; real-time intelligence; formidable air defence system; and early warning systems for its 'strategic denial' and 'total people's defence' doctrine.[71]

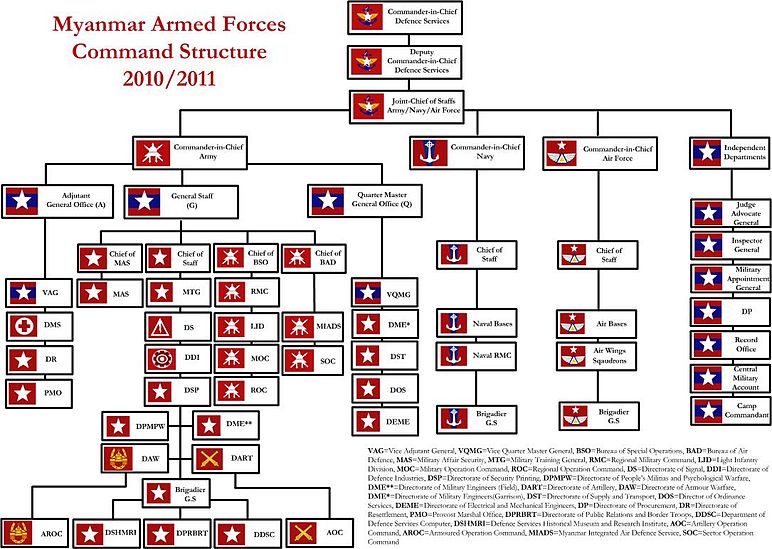

Organisational, command and control structure[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (February 2021) |

Before 1988[edit]

Overall command of Tatmadaw (armed forces) rested with the country's highest-ranking military officer, a general, who acted concurrently as defence minister and Chief of Staff of Defence Services. He thus exercised supreme operational control over all three services, under the direction of the President, State Council and Council of Ministers. There was also a National Security Council which acted in advisory capacity. The Defence Minister cum Chief-of-Staff of Defence Services exercised day-to-day control of the armed forces and assisted by three Vice-Chiefs of Staff, one each for the army, navy and air force. These officers also acted as Deputy Ministers of Defence and commanders of their respective Services. They were all based at Ministry of Defence (Kakweyay Wungyi Htana) in Rangoon/Yangon. It served as a government ministry as well as joint military operations headquarters.[72]

The Joint Staff within the Ministry of Defence consisted of three major branches, one each for Army, Navy and Air Force, along with a number of independent departments. The Army Office had three major departments; the General (G) Staff to oversee operations, the Adjutant General's (A) Staff administration and the Quartermaster General's (Q) Staff to handle logistics. The General Staff consisted two Bureaus of Special Operations (BSO), which were created in April 1978 and June 1979 respectively.[73]

These BSO are similar to "Army Groups" in Western armies, high level staff units formed to manage different theatres of military operations. They were responsible for the overall direction and co-ordination of the Regional Military Commands (RMC) with BSO-1 covering Northern Command (NC), North Eastern Command (NEC), North Western Command (NWC), Western Command (WC) and Eastern Command (EC). BSO-2 responsible for South Eastern Command (SEC), South Western Command (SWC), Western Command (WC) and Central Command (CC).[73]

The Army's elite mobile Light Infantry Divisions (LID) were managed separately under a staff colonel. Under G Staff, there were also a number of directorates which corresponded to the Army's functional corps, such as Intelligence, Signals, Training, Armour and Artillery. The A Staff was responsible for the Adjutant General, Directorate of Medical Services and the Provost Marshal's Office. The Q Staff included the Directorates of Supply and Transport, Ordnance Services, Electrical and Mechanical Engineering, and Military Engineers.

The Navy and Air Force Offices within the Ministry were headed by the Vice Chiefs of Staff for those Services. Each was supported by a staff officer at full colonel level. All these officers were responsible for the overall management of the various naval and air bases around the country, and the broader administrative functions such as recruitment and training.

Operational Command in the field was exercised through a framework of Regional Military Commands (RMC), the boundaries of which corresponded with the country's Seven States and Seven Divisions.[74] The Regional Military Commanders, all senior army officers, usually of Brigadier General rank, were responsible for the conduct of military operations in their respective RMC areas. Depending on the size of RMC and its operational requirements, Regional Military Commanders have at their disposal 10 or more infantry battalions (Kha La Ya).

1988 to 2005[edit]

The Tatmadaw's organisational and command structure dramatically changed after the military coup in 1988. In 1990, the country's most senior army officer become a senior general (equivalent to field marshal rank in Western armies) and held the positions of chairman of State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), prime minister and defence minister, as well as being appointed Commander in Chief of the Defence Services. He thus exercised both political and operational control over the entire country and armed forces.

From 1989, each service has had its own commander in chief and chief of staff. The Army Commander in Chief is now elevated to full general (Bo gyoke Kyii) rank and also acted as deputy commander in Chief of the Defence Services. The C-in-C of the Air Force and Navy hold the equivalent of lieutenant general rank, while all three Service Chiefs of Staff were raised to major general level. Chiefs of Bureau of Special Operations (BSO), the heads of Q and A Staffs and the Director of Defence Services Intelligence (DDSI) were also elevated to lieutenant general rank. The reorganisation of the armed forces after 1988 resulted in the upgrading by two ranks of most of the senior positions.

A new command structure was introduced at the Ministry of Defence level in 2002. The most important position created is the Joint Chief of Staff (Army, Navy, Air Force) that commands commanders-in-chief of the Navy and the Air Force.

The Office of Strategic Studies (OSS, or Sit Maha Byuha Leilaryay Htana) was formed around 1994 and charged with formulating defence policies, and planning and doctrine of the Tatmadaw. The OSS was commanded by Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt, who is also the Director of Defence Service Intelligence (DDSI). Regional Military Commands (RMC) and Light Infantry Divisions (LID) were also reorganised, and LIDs are now directly answerable to Commander in Chief of the Army.

A number of new subordinate command headquarters were formed in response to the growth and reorganisation of the Army. These include Regional Operation Commands (ROC, or Da Ka Sa), which are subordinate to RMCs, and Military Operations Commands (MOC, or Sa Ka Kha), which are equivalent to Western infantry divisions.

The Chief of Staff (Army) retained control of the Directorates of Signals, Directorate of Armour Corps, Directorate of Artillery Corps, Defence Industries, Security Printing, Public Relations and Psychological Warfare, and Military Engineering (field section), People's Militias and Border Troops, Directorate of Defence Services Computers (DDSC), the Defence Services Museum and Historical Research Institute.

Under the Adjutant General Office, there are three directorates: Medical Services, Resettlement, and Provost Martial. Under the Quartermaster General Office are the directorates of Military Engineering (garrison section), Supply and Transport, Ordnance Services, and Electricaland Mechanical Engineering.

Other independent department within the Ministry of Defence are Judge Advocate General, Inspector General, Military Appointment General, Directorate of Procurement, Record Office, Central Military Accounting, and Camp Commandant.

All RMC Commander positions were raised to the level of major general and also serve as appointed chairmen of the state- and division-level Law and Order Restoration Committees. They were formally responsible for both military and civil administrative functions for their command areas. Also, three additional regional military commands were created. In early 1990, a new RMC was formed in Burma's north west, facing India. In 1996, the Eastern Command in Shan State was split into two RMCs, and South Eastern Command was divided to create a new RMC in country's far south coastal regions.[75]

In 1997, the SLORC was abolished and the military government created the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC). The council includes all senior military officers and commanders of the RMCs. A new Ministry of Military Affairs was established and headed by a lieutenant general. This new ministry was abolished after its minister Lt. Gen. Tin Hla was sacked in 2001.

2005 to 2010[edit]

On 18 October 2004, the OSS and DDSI were abolished during the purge of General Khin Nyunt and military intelligence units. OSS ordered 4 regiment to raid in DDSI Headquarter in Yangon. At the same time, all of the MIU in the whole country were raided and arrested by OSS corps. Nearly two thirds of MIU officers were detained for years. A new military intelligence unit called Military Affairs Security (MAS) was formed to take over the functions of the DDSI, but MAS units were much fewer than DDSI's and MAS was under control by local Division commander.

In early 2006, a new Regional Military Command (RMC) was created at the newly formed administrative capital, Naypyidaw.

Service branches[edit]

Myanmar Army (Tatmadaw Kyee)[edit]

The Myanmar Army has always been by far the largest service and has always received the lion's share of Burma's defence budget.[76][77] It has played the most prominent part in Burma's struggle against the 40 or more insurgent groups since 1948 and acquired a reputation as a tough and resourceful military force. In 1981, it was described as "probably the best army in Southeast Asia, apart from Vietnam's".[78] This judgment was echoed in 1983, when another observer noted that "Myanmar's infantry is generally rated as one of the toughest, most combat seasoned in Southeast Asia".[79]

Myanmar Air Force (Tatmadaw Lay)[edit]

Personnel: 23,000 [80]

The Myanmar Air Force was formed on 16 January 1947, while Myanmar (also known as Burma) was under British colonial rule. By 1948, the new air force fleet included 40 Airspeed Oxfords, 16 de Havilland Tiger Moths, 4 Austers and 3 Supermarine Spitfires transferred from Royal Air Force with a few hundred personnel. The primary mission of Myanmar Air Force since its inception has been to provide transport, logistical, and close air support to Myanmar Army in counter-insurgency operations.

[edit]

The Myanmar Navy is the naval branch of the armed forces of Burma with estimated 19,000 men and women. The Myanmar Navy was formed in 1940 and, although very small, played an active part in Allied operations against the Japanese during the Second World War. The Myanmar Navy currently operates more than 122 vessels. Before 1988, the Myanmar Navy was small and its role in the many counterinsurgency operations was much less conspicuous than those of the army and air force. Yet the navy has always been, and remains, an important factor in Burma's security and it was dramatically expanded in recent years to a provide blue water capability and external threat defence role in Burma's territorial waters. Its personnel number 19,000 (including two naval infantry battalions).[81]

Myanmar Police Force (Myanmar Ye Tat Hpwe)[edit]

The Myanmar Police Force, formally known as The People's Police Force (Burmese: ပြည်သူ့ရဲတပ်ဖွဲ့; MLCTS: Pyi Thu Yae Tup Pwe), was established in 1964 as independent department under the Ministry of Home Affairs. It was reorganised on 1 October 1995 and informally become part of Tatmadaw. Current director general of Myanmar Police Force is Brigadier General Kyaw Kyaw Tun with its headquarters at Naypyidaw. Its command structure is based on established civil jurisdictions. Each of Burma's seven states and seven divisions has their own Police Forces with headquarters in the respective capital cities.[82] Israel and Australia often provide specialists to enhance the training of Burma's police.[33] Personnel: 72,000 (including 4,500 Combat/SWAT Police)

Rank structure[edit]

Air Defence[edit]

The Myanmar Air Defense Forces (လေကြောင်းရန်ကာကွယ်ရေးတပ်ဖွဲ့) is one of the major branches of Tatmadaw. It was established as the Air Defence Command in 1997 but was not fully operational until late 1999. It was renamed the Bureau of Air Defence in the early 2000s. In early 2000s, Tatmadaw established the Myanmar Integrated Air Defence System (MIADS) (မြန်မာ့အလွှာစုံပေါင်းစပ်လေကြောင်းရန်ကာကွယ်ရေးစနစ်) with help from Russia, Ukraine and China. It is a tri-service bureau with units from all three branches of the armed forces. All air defence assets except anti-aircraft artillery are integrated into MIADS.[83]

Military intelligence[edit]

The Office of the Chief of Military Security Affairs (OCMSA), commonly referred to by its Burmese acronym Sa Ya Pha (စရဖ), is a branch of the Myanmar armed forces tasked with intelligence gathering. It was created to replace the Directorate of Defence Services Intelligence (DDSI), which was disbanded in 2004.[84]

Defence industries[edit]

The Myanmar Directorate of Defence Industries (DI) consists of 25 major factories throughout the country that produce approximately 70 major products for Army, Navy and Air Force.[85] The main products include automatic rifles, machine guns, sub-machine guns, anti-aircraft guns, complete range of mortar and artillery ammunition, aircraft and anti-aircraft ammunition, tank and anti-tank ammunition, bombs, grenades, anti-tank mines, anti-personnel mines such as the M14[86][87] pyrotechnics, commercial explosives and commercial products, and rockets and so forth. DI have produced new assault rifles and light machine-guns for the infantry. The MA series of weapons were designed to replace the old German-designed but locally manufactured Heckler & Koch G3s and G4s that equipped Burma's army since the 1960s.[33]

Political representation in Myanmar's legislature[edit]

25% of the seats in both houses of the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, Myanmar's legislature, are reserved for military appointees.

House of Nationalities (Amyotha Hluttaw)[edit]

| Election | Total seats reserved | Total votes | Share of votes | Outcome of election | Election leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 56 / 224

|

Than Shwe | |||

| (after) 2012 | 56 / 224

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

| 2015 | 56 / 224

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

| 2020 | 56 / 224

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

House of Representatives (Pyithu Hluttaw)[edit]

| Election | Total seats reserved | Total votes | Share of votes | Outcome of election | Election leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 110 / 440

|

Than Shwe | |||

| (after) 2012 | 110 / 440

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

| 2015 | 110 / 440

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

| 2020 | 110 / 440

|

Min Aung Hlaing | |||

See also[edit]

- Military intelligence of Myanmar

- Aung San

- Royal Burmese armed forces

- Military history of Myanmar

- Ma Chit Po

Notes[edit]

- ^ also the formation patch of Chiefs of Staffs’ offices each.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ "CINCDS Myanmar". Cincds.gov.mm. Archived from the original on 14 June 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ Armed Forces Day (Myanmar)

- ^ "Protégé of Myanmar Junta Boss Tipped to be His Successor as Military Chief". The Irrawaddy. 17 March 2022. Archived from the original on 7 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar's Military Is Smaller Than Commonly Thought — and Shrinking Fast". www.usip.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2023. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Border Guard Force Scheme". Myanmar Peace Monitor. 18 March 2020 [first published 11 January 2013]. Archived from the original on 21 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Maung Zaw (18 March 2016). "Taint of 1988 still lingers for rebooted student militia". Archived from the original on 19 February 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-increases-military-budget-to-us2-7-billion.html#:~:text=Myanmar's%20junta%20chief%20Min%20Aung,3.7%20trillion%20kyats%20last%20year.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Myanmar shipyard building 4th frigate". Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

- ^ https://www.irrawaddy.com/specials/junta-watch/junta-watch-belarus-seals-bloody-alliance-with-regime-resistance-hit-naypyitaw-touted-as-top-tourism-destination-and-more.html

- ^ a b c d e f g "7 countries still supplying arms to Myanmar military". Anadolu Agency. 5 August 2019. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-junta-turns-to-iran-for-missiles-and-drones.html

- ^ "Israel among 7 nations faulted in UN report for arming Myanmar army". Times of Israel. 5 August 2019. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Buchanan, John (July 2016). "Militias in Myanmar" (PDF). The Asia Foundation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2016.

- ^ Wudunn, Sheryl (11 December 1990). "New 'Burmese Way' Relies On Slogans From the Military (Published 1990)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Myanmar's 2015 landmark elections explained". BBC News. 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ a b "OHCHR | Myanmar: Tatmadaw leaders must be investigated for genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes – UN report". Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Myanmar's military accused of genocide in damning UN report". TheGuardian.com. 27 August 2018. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "U.N. Investigators Renew Call for Genocide Probe in Myanmar". Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "The World Isn't Prepared to Deal with Possible Genocide in Myanmar". The Atlantic. 28 August 2018. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ "Tatmadaw Claims Killed Karen Community Leader Was a Plainclothes Fighter". 11 April 2018. Archived from the original on 25 April 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Martin (1 December 2003). "The Enigma of Burma's Tatmadaw: A "State Within a State"". Critical Asian Studies. 35 (4): 621–632. doi:10.1080/1467271032000147069. S2CID 145060842.

- ^ Ebbighausen, Rodion (12 February 2021). "Myanmar's military: A state within a state". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 10 February 2023. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar" (PDF). Ministry of Information. September 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Steinberg 2009: 37

- ^ a b Hack, Retig 2006: 186

- ^ Dun 1980: 104

- ^ Steinberg 2009: 29

- ^ Seekins 2006: 124–126

- ^ Andrew Selth: Power Without Glory

- ^ Myoe, Maung Aung (22 January 2009). Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-230-848-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Maung Aung Myoe: Building of Tatmadaw

- ^ Maung Aung Myoe: Building the Tatmadaw

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Maung, Aung Myoe (2009). Building the Tatmadaw: Myanmar Armed Forces Since 1948. ISBN 978-981-230-848-1.

- ^ Mya Win - Leaders of Tatmadaw

- ^ Mya Win: Leaders of Tatmadaw

- ^ Dr. Maung Maung: General Ne Win and Burma

- ^ Martin Smith (1991). Burma – Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books.

- ^ Dictator Ne Win threatening speech to the people in 1988. Myanmar Radio and Television. 23 July 1988. Archived from the original on 7 June 2014.

- ^ "Burmese voice anger on poll day". BBC News. 10 May 2008. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Allchin, Joseph (10 January 2011). "Burma introduces military draft". www.dvb.no. Democratic Voice of Burma. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Myanmar and major powers: shifts in ties with China, Russia and the US". The Straits Times. 22 April 2017. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "Opinion | How Should the US Engage Myanmar?". The Irrawaddy. 9 February 2018. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "Myanmar parliament passes military cooperation plan with Russia". VOV – VOV Online Newspaper. 12 May 2016. Retrieved 4 July 2018.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Russia, Myanmar Sign Military Cooperation Agreement". www.defenseworld.net. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "Defence cooperation with Myanmar—Australia and other countries: a quick guide". www.aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "US House Backs Measures to Sanction Myanmar's Military, Nudge Gem Sector Reform". The Irrawaddy. 25 May 2018. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ "Myanmar companies bankroll 'brutal operations' of military, independent UN experts claim in new report". 5 August 2019. Archived from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ "After ASEAN & India, Now Myanmar Accuses China Of Creating Trouble On The Border". EurAsian Times. 30 June 2020. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar military takes control of country after detaining Aung San Suu Kyi". BBC News. February 2021. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ "Urgent: Myanmar forms caretaker government: State Administration Council". Xinhua | English.news.cn. 1 August 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Myanmar military leader takes new title of prime minister in caretaker government – state media". Reuters. 1 August 2021. Archived from the original on 1 August 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Myanmar military extends emergency, promises vote in 2 years". AP NEWS. 1 August 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ "Texts adopted – Myanmar, one year after the coup – Thursday, 10 March 2022". Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "China, Russia arming Myanmar junta, UN expert says | DW | 22.02.2022". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Hein, Ye Myo. "Myanmar's Military Is Smaller Than Commonly Thought — and Shrinking Fast A lack of reliable data has le". United States Institute for Peace. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

- ^ Myers, Lucas. "THE MYANMAR MILITARY IS FACING DEATH BY A THOUSAND CUTS". War on the Rocks. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Abuza, Zachary. "Signs of desperation as the Myanmar junta rotates commanders". Radio Free Asia. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ "Analysis | Tracking the Myanmar Govt's Income Sources and Spending". The Irrawaddy. 22 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Freedom in the World 2017 – Myanmar". Freedom House. 1 January 2017. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "MP points out lack of details about defence spending". The Myanmar Times. 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Economic interests of the Myanmar military". United Nations Human Rights Council. 16 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ McCarthy, Gerard (6 March 2019). Military Capitalism in Myanmar: Examining the Origins, Continuities and Evolution of "Khaki Capital". ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute. ISBN 978-981-4843-55-3.

- ^ "Myanmar military gets billions from profitable business: Amnesty". Al Jazeera. 10 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "Spending on electricity tops budget for the first time". The Myanmar Times. 10 October 2019. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ "Myanmar parliament cuts Defence Ministry budget by K10.6 billion". The Myanmar Times. 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ ဝင်းကိုကိုလတ် (28 October 2014). "စစ်ဆင်ရေးအတွက် ကန်ဒေါ်လာ ရှစ်ဘီလီယံသုံး". Mizzima (in Burmese). Archived from the original on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ Aung San Thuriya Hla Thaung (Armanthit Sarpay, Yangon, 1999)

- ^ In Defiance of the Storm (Myawaddy Press, Yangon, 1997

- ^ Strategic Cultures in Asia-Pacific Region (St. Martin's Press)

- ^ Italic text

- ^ a b c d e f Andrew Selth, Burma's Armed Forces

- ^ Andrew Selth: Transforming the Tatmadaw

- ^ a b Maung Aung Myoe: Building the Tatmadaw, p.26

- ^ See order of battle for further details

- ^ see Order of Battle for further details

- ^ Working Papers – Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, ANU

- ^ Andrew Selth: Power Without Glory

- ^ Far Eastern Economic Review, 20 May 1981

- ^ Far Eastern Economic Review, 7 July 1983

- ^ Myoe, Maung Aung: Building Tatmadaw

- ^ Myoe, Maung Aung: Building the Tatmadaw

- ^ http://www.myanmar.gov.mm/ministry/home/mpf/[permanent dead link]

- ^ IndraStra Global Editorial Team (30 October 2020). "Myanmar Integrated Air Defense System". Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ Paing, Yan (9 September 2014). "Burmese Military Reshuffle Sees New Security Chief Appointed". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 7 December 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- ^ Mathieson, David Scott (16 January 2023). "Targeting Myanmar's factories of death". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "Karen Human Rights Group | KHRG Photo Gallery 2008 | Landmines, mortars, army camps and soldiers". Archived from the original on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ "Asia Times Online :: Southeast Asia news – Myanmar, the world's landmine capital". Archived from the original on 29 December 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Sources[edit]

- Dun, Smith (1980). Memoirs of the Four-Foot Colonel, Volumes 113–116. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University SEAP Publications. ISBN 978-0-87727-113-0.

- Hack, Karl; Tobias Rettig (2006). Colonial armies in Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415334136.

- Seekins, Donald M. (2006). Historical dictionary of Burma (Myanmar), vol. 59 of Asian/Oceanian historical dictionaries. Vol. 59 (Illustrated ed.). Sacredcrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5476-5.

- Steinberg, David I. (2009). Burma/Myanmar: what everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195390681.

.svg/100px-Southeast_Asia_(orthographic_projection).svg.png)