Northern and southern China

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Northern China (Chinese: 中国北方 or 中国北部; lit. 'China's North') and Southern China (Chinese: 中国南方 or 中国南部; lit. 'China's South')[note 1] are two approximate regions within China. The exact boundary between these two regions is not precisely defined and only serve to depict where there appears to be regional differences between the climates and localities of northern regions of China vs southern regions of China. Nevertheless, regional differences in culture and language have historically fostered a number of local identities.[1][2]

Extent[edit]

Often used as the geographical dividing line between northern and southern China is the Qinling–Huaihe Line (lit. Qin Mountains–Huai River Line). This line approximates the 0 °C January isotherm and the 800 millimetres (31 in) isohyet in China.

Culturally, however, the division is more ambiguous. In the eastern provinces like Jiangsu and Anhui, the Yangtze River may instead be perceived as the north–south boundary instead of the Huai River, but this is a recent development.

There is an ambiguous area, the Nanyang Basin region in Henan, that lies in the gap where the Qin has ended and the Huai River has not yet begun; also, central Anhui and Jiangsu lie south of the Huai River but north of the Yangtze, making their classification somewhat ambiguous as well. As such, the boundary between northern and southern China does not follow provincial boundaries; it cuts through Shaanxi, Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu, and creates areas such as Hanzhong (Shaanxi), Xinyang (Henan), Huaibei (Anhui) and Xuzhou (Jiangsu) that lie on the opposite half of China from the rest of their respective provinces. This may have been deliberate; the Yuan dynasty and Ming dynasty established many of these boundaries intentionally to discourage anti-dynastic regionalism.[citation needed]

The Northeast and Inner Mongolia are conceived to belong to northern China according to the framework above. At some times in history, Xinjiang, Tibet and Qinghai were not conceived of as being part of either the north or south. However, internal migration, such as between the Shandong and Liaodong peninsulas during the Chuang Guandong period, have increased the purview of "north" China to include previously marginalized areas.

History[edit]

The concepts of northern and southern China originate from differences in climate, geography, culture, and physical traits; as well as several periods of actual political division in history. Northern and northeastern China is considered too cold and dry for rice cultivation (though rice is grown there today with the aid of modern technology) and consists largely of flat plains, grasslands, and desert; while southern China is warm and rainy enough for rice and consists of lush mountains cut by river valleys. Historically, these differences have led to differences in warfare during the pre-modern era, as cavalry could easily dominate the northern plains but encountered difficulties against river navies fielded in the south. There are also major differences in cuisine, culture, and popular entertainment forms such as opera.

Episodes of division into North and South include:

- Three Kingdoms (220–280)

- Sixteen Kingdoms (317–420) and Southern and Northern Dynasties (420–589)[4]

- Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960)

- Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279) and Jin dynasty (1115–1234)

- Warlord era (1916–1928) of the Republic of China

The Northern and Southern Dynasties showed such a high level of polarization between North and South that sometimes northerners and southerners referred to each other as barbarians; subjects of the Yuan dynasty were divided into four political status classes. Northerners included the Khitans and other ethnic groups occupy the third-caste and southern natives occupying the lowest one.

For a large part of Chinese history, northern China was economically more advanced than southern China.[citation needed] The Jin and Yuan invasions caused a massive migration to southern China, and the Emperor shifted the Song dynasty capital city from Kaifeng in northern China to Hangzhou, located south of the Yangtze River. The population of Shanghai increased from 12,000 households to over 250,000 inhabitants after Kaifeng was sacked by invading armies. This began a shift of political, economic, and cultural power from northern China to southern China. The east coast of southern China remained a leading economic and cultural center of China until the Republic of China. Today, southern China remains economically more prosperous than northern China.

During the Qing dynasty, regional differences and identification in China fostered the growth of regional stereotypes. Such stereotypes often appeared in historic chronicles and gazetteers and were based on geographic circumstances, historical and literary associations (e.g. people from Shandong, were considered upright and honest) and Chinese cosmology (as the south was associated with the fire element, Southerners were considered hot-tempered).[1] These differences were reflected in Qing dynasty policies, such as the prohibition on local officials to serve their home areas, as well as conduct of personal and commercial relations.[1] In 1730, the Kangxi Emperor made the observation in the Tingxun Geyan (庭訓格言):[1][5]

The people of the North are strong; they must not copy the fancy diets of the Southerners, who are physically frail, live in a different environment, and have different stomachs and bowels.

— the Kangxi Emperor, Tingxun Geyan (《庭訓格言》)

During the Republican period, Lu Xun, a major Chinese writer, wrote:[6]

According to my observation, Northerners are sincere and honest; Southerners are skilled and quick-minded. These are their respective virtues. Yet sincerity and honesty lead to stupidity, whereas skillfulness and quick-mindedness lead to duplicity.

— Lu Xun, Complete works of Lu Xun (《魯迅全集》), pp. 493–495.

Today[edit]

In modern times, North and South are merely one of the ways that Chinese people identify themselves, and the divide between northern and southern China has been complicated both by a unified Chinese nationalism as well as by local loyalties to linguistically and culturally distinct regions within the province, prefecture, county, town and village isolates which prevent a coherent Northern or Southern identity from forming.

During the Deng Xiaoping reforms of the 1980s, South China developed much more quickly than North China, leading some scholars to wonder whether the economic fault line would create political tension between north and south. Some of this was based on the idea that there would be a conflict between the bureaucratic north and the commercial south. This has not occurred to the degree feared, in part because the economic fault lines eventually created divisions between coastal China and the interior, as well as between urban and rural China, which run in different directions from the north–south division, and in part because neither north nor south has any type of obvious advantage within the Chinese central government. Besides, there are other cultural divisions that exist within and across the north–south dichotomy.

Differences[edit]

Nevertheless, the concepts of North and South continue to play an important role in regional stereotypes. Some of these observations were made by Jones Lamprey, a British army surgeon in 1868.[7][8]

"Northerners" are seen as:

- Speaking Mandarin Chinese with a northern (rhotic) accent.

- More likely to eat noodles, dumplings and wheat-based foods[9] (rather than rice-based foods).[10][11]

- Taller than Southerners.[12]

- May have lighter skin tones.

While "Southerners" are seen as:

- Speaking Mandarin Chinese with a southern (non-rhotic) accent or speaking any southern Chinese language, such as Yue (e.g. Cantonese), Min (e.g. Hokkien), Wu (e.g. Shanghainese), Hakka, Xiang or Gan.

- More likely to eat rice-based foods (rather than wheat-based foods) and seafood.[10][9][11]

- Shorter than Northerners.[12]

- May have darker skin tones.

These are seen as stereotypes among a large and varied population. An individual's skin tone for example can change greatly from season to season depending on the extent of manual labor outdoors and their exposure to the sun. The intelligibility of dialects can also vary from one village to the next.[8]

Climate[edit]

Northern regions of China have winters that are cold and dry. The southern regions can have summers that are very hot and humid.[13] They are closer to the tropics and experience the East Asian monsoon.[14][better source needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Also referred to in China as simply the north (Chinese: 北方; pinyin: Běifāng) and the south (Chinese: 南方; pinyin: Nánfāng).

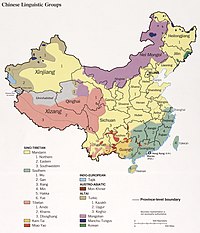

- ^ The map shows the distribution of linguistic groups according to the historical majority ethnic groups by region. Note this is different from the current distribution due to age-long internal migration and assimilation.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Smith, Richard Joseph (1994). China's cultural heritage: the Qing dynasty, 1644–1912 (2 ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-1347-4.

- ^ Xuefeng, He (7 March 2022). Northern and Southern China: Regional Differences in Rural Areas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-40262-9.

- ^ Source: United States Central Intelligence Agency, 1990.

- ^ Lewis, Mark Edward (30 April 2011). China Between Empires: The Northern and Southern Dynasties. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06035-7.

- ^ Hanson, Marta E. (July 2007). "Jesuits and Medicine in the Kangxi Court (1662–1722)" (PDF). Pacific Rim Report. San Francisco: Center for the Pacific Rim, University of San Francisco (43): 7, 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Young, Lung-Chang (Summer 1988). "Regional Stereotypes in China". Chinese Studies in History. 21 (4): 32–57. doi:10.2753/csh0009-4633210432. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ "Jones Lamprey | Historical Photographs of China". hpcbristol.net. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ a b Lamprey, J. (1868). "A Contribution to the Ethnology of the Chinese". Transactions of the Ethnological Society of London. 6: 101–108. doi:10.2307/3014248. ISSN 1368-0366.

- ^ a b Eberhard, Wolfram (December 1965). "Chinese Regional Stereotypes". Asian Survey. University of California Press. 5 (12): 596–608. doi:10.2307/2642652. JSTOR 2642652.

- ^ a b Fodor's (2009). Kelly, Margaret (ed.). Fodor's China. Fodor's Travel Publications. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4000-0825-4.

- ^ a b Regions of Chinese food-styles/flavours of cooking, University of Kansas

- ^ a b Lu, Guoguang; Yang, Zhihui; Zhang, Yan; Lu, Shengxu; Gong, Siyuan; Li, Tingting; Shen, Yijie; Zhang, Sihan; Zhuang, Hanya (2022). "Geographic latitude and human height - Statistical analysis and case studies from China". Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 15 (335). doi:10.1007/s12517-021-09335-x.

- ^ "Weather in China - Everything You Need to Know". First Leap China. 22 April 2019. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ Zhu, Hua (1 March 2017). "The Tropical Forests of Southern China and Conservation of Biodiversity". The Botanical Review. 83 (1): 87–105. doi:10.1007/s12229-017-9177-2. ISSN 1874-9372. S2CID 29536766.

Sources[edit]

- Brues, Alice Mossie (1977). People and Races. Macmillan series in physical anthropology. New York, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-315670-0.

- Muensterberger, Warner (1951). "Orality and Dependence: Characteristics of Southern Chinese." In Psychoanalysis and the Social Sciences, (3), ed. Geza Roheim (New York: International Universities Press).

Further reading[edit]

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Liu, Kwang-chang. (1999). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, Stephen L. (July 2000). "Richer and Taller: Stature and Living Standards in China, 1979-1995". The China Journal. doi:10.2307/2667475 – via JSTOR.

- Tu, Jo-fu. (1992). Chinese Surnames and the Genetic Differences Between North and South China. Project on Linguistic Analysis, University of California, Berkeley.